Post by motm on Sept 29, 2016 14:09:11 GMT -6

Is the Minnesota Vikings’ defense on the verge of something special, and can it carry the team to postseason success?

Right now the Vikings defense is playing at an incredibly high level. They lead the league in yards per play surrendered, at just 4.4, and have conceded just 13.3 points per game—despite an offense that hasn’t always held up its end of the bargain, and facing 33 more snaps this season than either of the two teams with a better points-per-game figure.

Only the Philadelphia Eagles have a better point-per-play mark than the Vikings through three games, and Minnesota just forced the reigning NFL MVP to have his worst game since Week 7 of last year.

Cam Newton ended the game against Minnesota with three interceptions to his name, two sacks charged to him, and an NFL passer rating of 47.6. That passer rating was just 13.1 when pressured, which happened on almost half of his dropbacks (48.9 percent). Though he did have a rushing touchdown, Newton was held to just 3.7 yards per carry against the Vikings, down from 5.4 over the first two games, and 4.9 over the 2015 season. By any measure, he was conclusively dominated by the Minnesota defense.

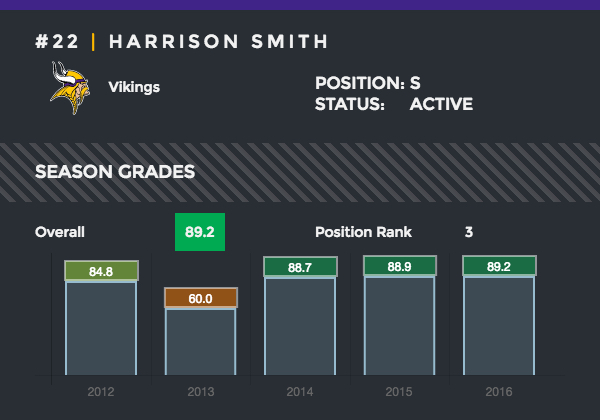

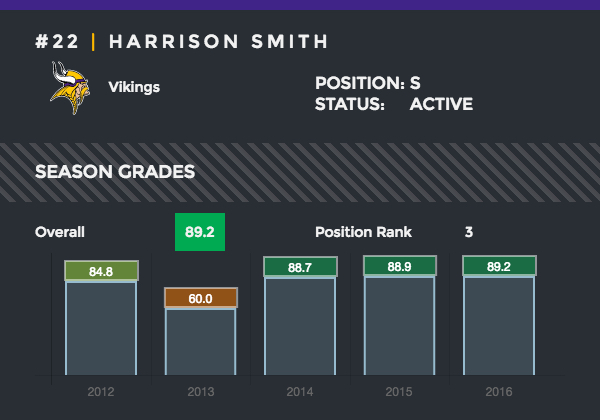

Obviously the Vikings have a lot of talent on defense and many players that are performing well right now. Harrison Smith may be the league’s best safety—sitting third among safeties this season in terms of overall grade, with an 89.2, a year after leading the position at 88.8—and is an incredibly versatile player that is at the heart of what the team does in coverage.

DE Danielle Hunter, DT Tom Johnson, and CB Terence Newman, among others, have all had strong starts to the season, but let’s dig a little deeper into what makes this unit greater than the sum of its parts, because there are multiple other defenses grading better from an individual standpoint through three games.

Multiple coverages:

The Vikings don’t actually roll their coverages often when it comes to disguises. One of the biggest keys for a QB reading a defense is whether the middle of the field is open or closed. With coverage schemes, one of the differentiators between them is how many deep zones there are. Cover-1 and cover-3 each have a deep free safety in the middle of the field, but cover-2, 4, or 6 will have two safeties deep, opening the middle of the field for post routes.

That simple read allows a quarterback to narrow down his options and start to work on secondary keys to determine exactly what coverage he is looking at. Because this is something a QB can read as he comes to the line before the ball is snapped, some teams will show one thing pre-snap, and roll to something else after it, showing either an open or closed middle of the field to the QB and switching to the other after the ball has been snapped.

Typically, the Vikings don’t do too much of that. Against Carolina, they only showed one thing and then switched to the other three times when it comes to the middle of the field being open/closed. What they do very well, however, is use a variety of different coverages within similar looks.

On 46 of Carolina’s dropbacks, Minnesota cycled through cover-1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 2-man, and even a snap in true prevent defense on the final defensive play. Some of these they used more heavily than others, but as a team, they are very good at mixing up the man and zone aspects of coverage and trying to play matchup defense with receivers in coverage.

Integrating with the defensive front:

Where the Vikings are exceptionally good is in linking this coverage disguise with the blitz and the pass-rush up front.

Pass-rush and coverage have an important connection, because the quicker you can pressure the QB, the less time defenders have to cover their receivers and the more chance an errant pass comes out. On the flip-side, the better the coverage is, the longer the QB has to hold the ball to find an open man, and the more time that buys the pass-rush to get home. The Vikings integrate the two sides far more than that natural symbiotic relationship.

Minnesota will stack the line of scrimmage and make it very difficult for the offense to know who is coming after the QB, who is dropping into coverage, and what that coverage will look like when they do. They actually meld the pass-rush and coverage at or around the line of scrimmage to confuse the offense and make it difficult to identify which players at the line are part of which aspect of the defense on the play.

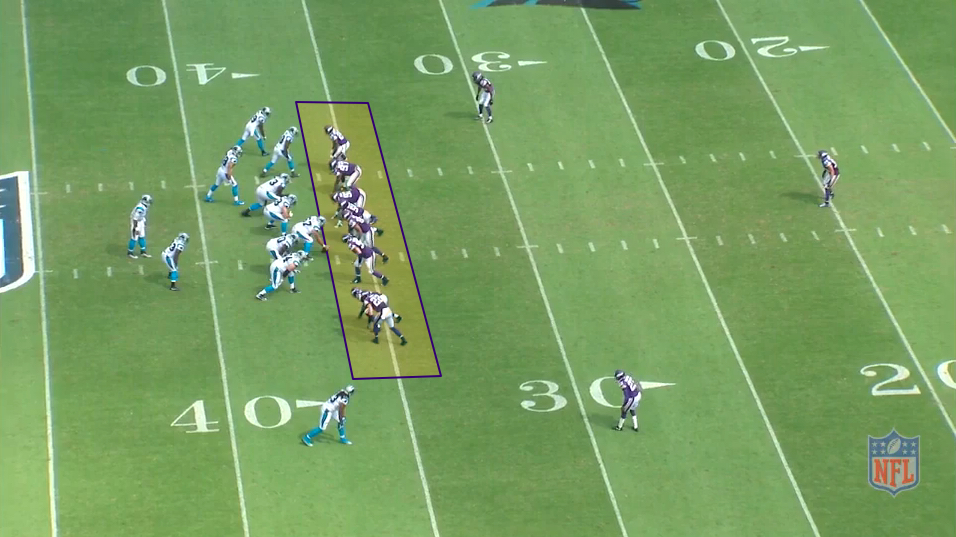

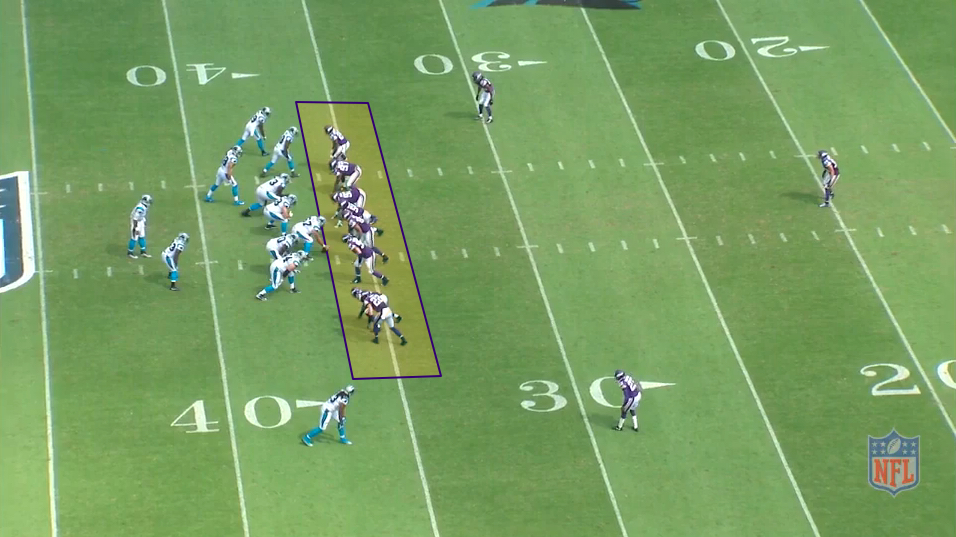

Take this play as an example mid-way through the first quarter against the Panthers:

The Vikings have eight guys up at the line of scrimmage, with just three deep coverage defenders as a pre-snap look. Any of those eight defenders could be rushing the passer in any number, which becomes a very difficult thing for the offense to diagnose and contend with.

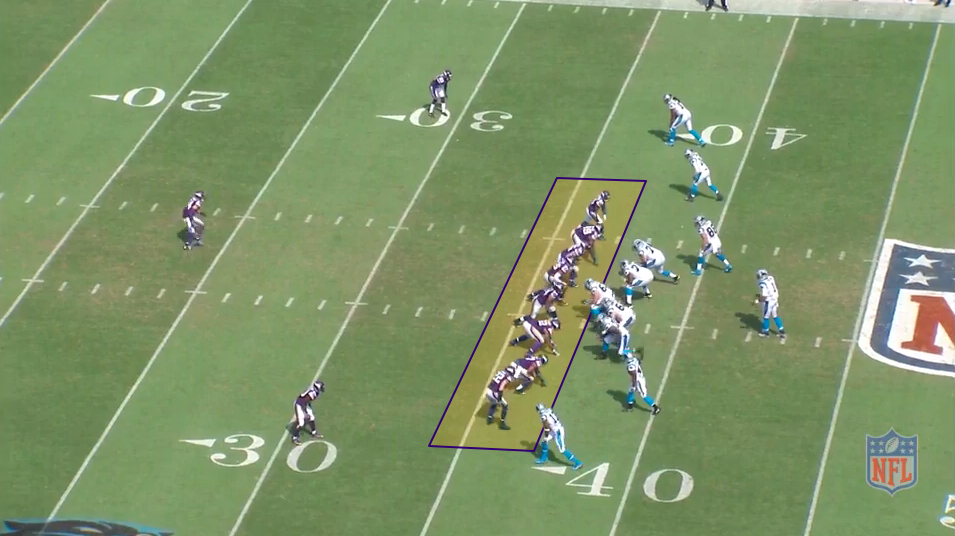

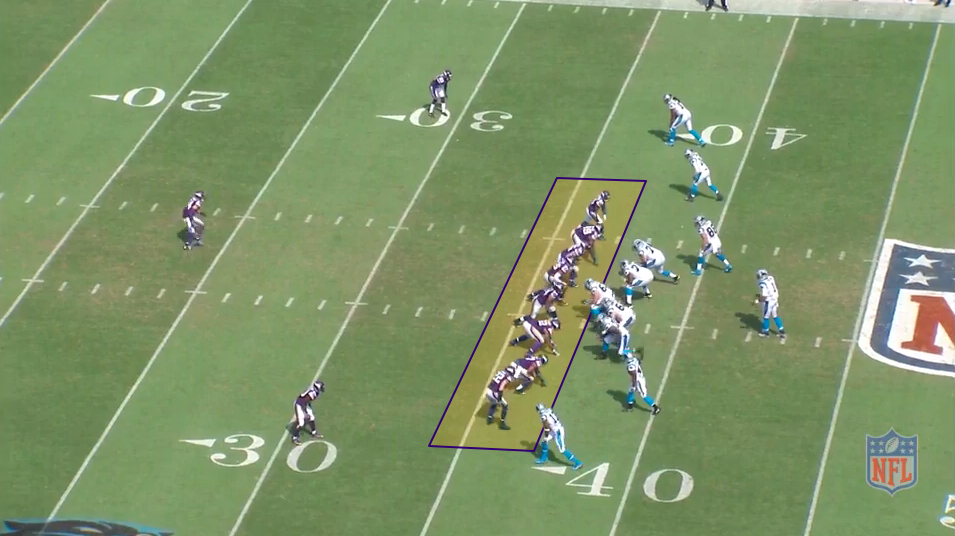

Later in the game, they showed the same kind of front, with both linebackers lined up in the A-gaps up front, and the same eight defenders at the line.

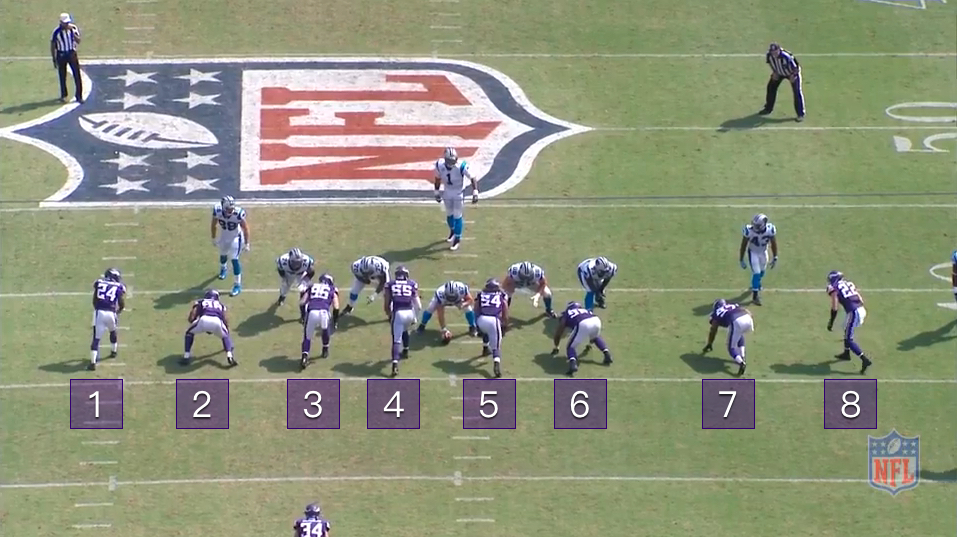

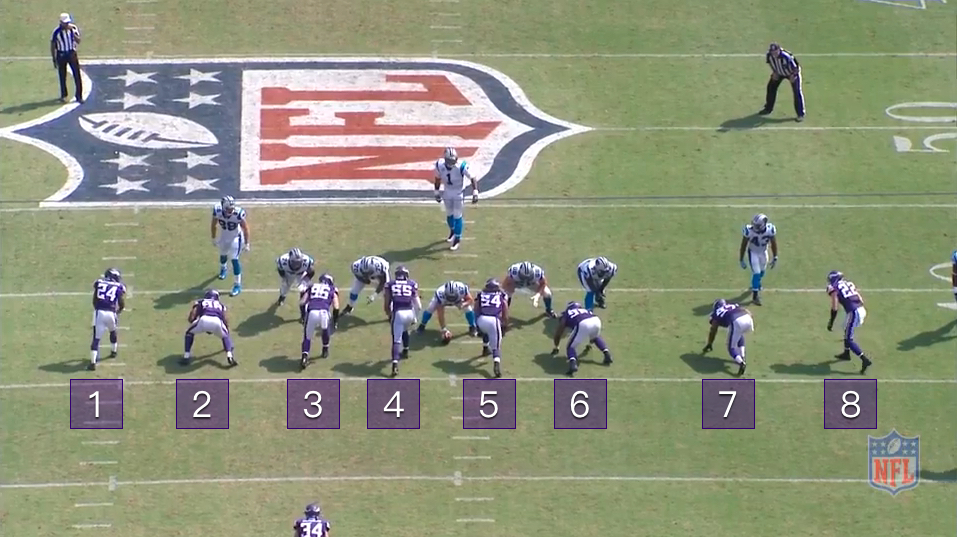

When you look at the play pre-snap from the end-zone view, you can see the Vikings have somebody stationed in every single gap along the Panthers’ line, which is where the problem arises. The Panthers are looking at eight guys, each of whom is a viable threat to rush because they each have a different gap; even if Carolina keeps everybody at home to block, they can only pick up seven of them.

This time, six Vikings’ defenders rushed—both a different number and a different combination of rushers than the last time, causing quick pressure on Newton.

If you look at the players involved at the line, four of them are defensive linemen, two are linebackers, and two are defensive backs. In personnel-package terms, the Vikings are in standard nickel defense that should look like a vanilla 4-2-5 deployment on the field. By stacking the line of scrimmage like this, however, the Panthers can’t determine which of the defenders is which, because both of the defensive backs could be rushing the passer instead of covering, with their places in shallow zones or bracketing receivers taken by the linebackers (or even the defensive linemen) on a zone blitz.

Part of keeping the offense off balance is varying not just the players that rush the passer, but how many are coming at any one time. The Vikings won’t play every coverage as it’s drawn up on the chalkboard, but at times, they only need to keep as many players in coverage as they need to cover the receivers in routes. Against Carolina, they rushed four players 27 times, a little more than half of the snaps. They rushed five on 11 snaps (22 percent), six on six snaps (12 percent), and seven once.

Bottom line:

Right now, the Vikings’ defense is playing even better than a year ago, but on an individual level, they aren’t quite matching those performances (with the exception of Harrison Smith on the back end). Last season, Linval Joseph and Anthony Barr, among others, were dominating in a way they haven’t yet this season. That could go one of two ways for this team going forward in 2016; either those players begin to improve individually, and this defense has even more to come, or eventually the smoke-and-mirrors tricks of Minnesota’s scheme start to fail against opposing offenses, and the defense will be unable to match the blistering pace it has set early in the year.

Right now, though, the Vikings’ defense is one of the toughest in the league to cope with, both because of solid personnel and exceptionally-challenging schemes for offenses to diagnose and react to.

Link: www.profootballfocus.com/pro-why-minnesotas-defense-has-been-so-successful-this-season/

Right now the Vikings defense is playing at an incredibly high level. They lead the league in yards per play surrendered, at just 4.4, and have conceded just 13.3 points per game—despite an offense that hasn’t always held up its end of the bargain, and facing 33 more snaps this season than either of the two teams with a better points-per-game figure.

Only the Philadelphia Eagles have a better point-per-play mark than the Vikings through three games, and Minnesota just forced the reigning NFL MVP to have his worst game since Week 7 of last year.

Cam Newton ended the game against Minnesota with three interceptions to his name, two sacks charged to him, and an NFL passer rating of 47.6. That passer rating was just 13.1 when pressured, which happened on almost half of his dropbacks (48.9 percent). Though he did have a rushing touchdown, Newton was held to just 3.7 yards per carry against the Vikings, down from 5.4 over the first two games, and 4.9 over the 2015 season. By any measure, he was conclusively dominated by the Minnesota defense.

Obviously the Vikings have a lot of talent on defense and many players that are performing well right now. Harrison Smith may be the league’s best safety—sitting third among safeties this season in terms of overall grade, with an 89.2, a year after leading the position at 88.8—and is an incredibly versatile player that is at the heart of what the team does in coverage.

DE Danielle Hunter, DT Tom Johnson, and CB Terence Newman, among others, have all had strong starts to the season, but let’s dig a little deeper into what makes this unit greater than the sum of its parts, because there are multiple other defenses grading better from an individual standpoint through three games.

Multiple coverages:

The Vikings don’t actually roll their coverages often when it comes to disguises. One of the biggest keys for a QB reading a defense is whether the middle of the field is open or closed. With coverage schemes, one of the differentiators between them is how many deep zones there are. Cover-1 and cover-3 each have a deep free safety in the middle of the field, but cover-2, 4, or 6 will have two safeties deep, opening the middle of the field for post routes.

That simple read allows a quarterback to narrow down his options and start to work on secondary keys to determine exactly what coverage he is looking at. Because this is something a QB can read as he comes to the line before the ball is snapped, some teams will show one thing pre-snap, and roll to something else after it, showing either an open or closed middle of the field to the QB and switching to the other after the ball has been snapped.

Typically, the Vikings don’t do too much of that. Against Carolina, they only showed one thing and then switched to the other three times when it comes to the middle of the field being open/closed. What they do very well, however, is use a variety of different coverages within similar looks.

On 46 of Carolina’s dropbacks, Minnesota cycled through cover-1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 2-man, and even a snap in true prevent defense on the final defensive play. Some of these they used more heavily than others, but as a team, they are very good at mixing up the man and zone aspects of coverage and trying to play matchup defense with receivers in coverage.

Integrating with the defensive front:

Where the Vikings are exceptionally good is in linking this coverage disguise with the blitz and the pass-rush up front.

Pass-rush and coverage have an important connection, because the quicker you can pressure the QB, the less time defenders have to cover their receivers and the more chance an errant pass comes out. On the flip-side, the better the coverage is, the longer the QB has to hold the ball to find an open man, and the more time that buys the pass-rush to get home. The Vikings integrate the two sides far more than that natural symbiotic relationship.

Minnesota will stack the line of scrimmage and make it very difficult for the offense to know who is coming after the QB, who is dropping into coverage, and what that coverage will look like when they do. They actually meld the pass-rush and coverage at or around the line of scrimmage to confuse the offense and make it difficult to identify which players at the line are part of which aspect of the defense on the play.

Take this play as an example mid-way through the first quarter against the Panthers:

The Vikings have eight guys up at the line of scrimmage, with just three deep coverage defenders as a pre-snap look. Any of those eight defenders could be rushing the passer in any number, which becomes a very difficult thing for the offense to diagnose and contend with.

Later in the game, they showed the same kind of front, with both linebackers lined up in the A-gaps up front, and the same eight defenders at the line.

When you look at the play pre-snap from the end-zone view, you can see the Vikings have somebody stationed in every single gap along the Panthers’ line, which is where the problem arises. The Panthers are looking at eight guys, each of whom is a viable threat to rush because they each have a different gap; even if Carolina keeps everybody at home to block, they can only pick up seven of them.

This time, six Vikings’ defenders rushed—both a different number and a different combination of rushers than the last time, causing quick pressure on Newton.

If you look at the players involved at the line, four of them are defensive linemen, two are linebackers, and two are defensive backs. In personnel-package terms, the Vikings are in standard nickel defense that should look like a vanilla 4-2-5 deployment on the field. By stacking the line of scrimmage like this, however, the Panthers can’t determine which of the defenders is which, because both of the defensive backs could be rushing the passer instead of covering, with their places in shallow zones or bracketing receivers taken by the linebackers (or even the defensive linemen) on a zone blitz.

Part of keeping the offense off balance is varying not just the players that rush the passer, but how many are coming at any one time. The Vikings won’t play every coverage as it’s drawn up on the chalkboard, but at times, they only need to keep as many players in coverage as they need to cover the receivers in routes. Against Carolina, they rushed four players 27 times, a little more than half of the snaps. They rushed five on 11 snaps (22 percent), six on six snaps (12 percent), and seven once.

Bottom line:

Right now, the Vikings’ defense is playing even better than a year ago, but on an individual level, they aren’t quite matching those performances (with the exception of Harrison Smith on the back end). Last season, Linval Joseph and Anthony Barr, among others, were dominating in a way they haven’t yet this season. That could go one of two ways for this team going forward in 2016; either those players begin to improve individually, and this defense has even more to come, or eventually the smoke-and-mirrors tricks of Minnesota’s scheme start to fail against opposing offenses, and the defense will be unable to match the blistering pace it has set early in the year.

Right now, though, the Vikings’ defense is one of the toughest in the league to cope with, both because of solid personnel and exceptionally-challenging schemes for offenses to diagnose and react to.

Link: www.profootballfocus.com/pro-why-minnesotas-defense-has-been-so-successful-this-season/